Photographs document the history of our town. Thanks to practitioners of this once technically complicated craft we can time travel to moments during the shipbuilding boom and to the birth of our "cottage" industry. A gifted practitioner can portray much more about the character of a place and the nature of the lives lived there.

Kennebunkport photographer Byron James Whitcomb was one such artist. He grew up in Readsboro, Vermont, a tiny mountain town near the border of Massachusetts, the son of Frank and Nellie Whitcomb. At the age of ten he started working to help support his family and while still in school was the sole support of his household. His first trade was carpentry and as a very young man he built and sold several houses. The Spanish American War presented his second occupation and he served throughout the conflict. After the War he studied Photography in Athol, MA.

If we believe the pictures he took as a young man his family lived modestly but enjoyed extravagant laughter and affection for one another. Metta Inez Dunklee, a Vermont girl became his wife in 1900. She was also a talented photographer. The couple gained professional experience working for state-of-the-art photography studios in Boston and briefly in a studio of their own in Bristol, NH.

Kennebunk photographer, Lawrence X. Champou was anxious to retire in the autumn of 1902. He traveled to "the best studios of Boston" and returned with a buyer for his business at the corner of Main St. and Fletcher St. The two-story building was owned by S. T. Fuller and stood where the Civil War Monument now stands beside the bank. The first floor was Littlefield and Weber grocery and the second floor was the photographic business, which Champou had bought from photographer Leo N. Hill in 1900.

B. J. and Inez Whitcomb moved to Kennebunk with Byron’s mother and sister Bessie whom they continued to support. The studio faced the challenge of establishing a reputation in town and for several months they struggled to keep the business afloat.

The competition, Albion Moody, had come to town in 1880 to work in the shoe factory and he and his daughter Lillie had a humble little photographic studio at the west end of the bridge over the Mousam River. Moody’s business was sporadic by 1902 and he and his daughter continued to work in the factory off and on. Early in 1903 Albion Moody suffered an extended attack of "Le Grippe", a respiratory virus that would plague him for the rest of his life. Lillie held the fort for the months that Moody was unable to work but the studio was often closed to business.

May 3, 1903 fire took the largest employer in town, the factory. It also consumed the light plant and many of the buildings at the bridge in Kennebunk. No lives were lost but the impact on the economy of Kennebunk was significant. Whitcomb was at the scene of the fire and captured the devastation with his camera. The drama of those photographs would ensure his reputation in Kennebunk as a gifted photographer. He also offered portraits of a cat that had miraculously survived the blaze who became a symbol of hope for the future of Kennebunk and sales were brisk for the remainder of 1903; So brisk in fact that the Whitcombs were able to take an extended working vacation in Boston during early 1904.

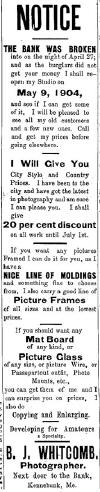

On April 28, 1904, thieves attempted to blow open the safe at the Bank next door to the Whitcomb’s studio. They were chased away by an alert neighbor. The following week Byron purchased an ad in "The Local News" to announce that he was back from his vacation and ready to again do business. His ad read "The bank was broken into on the night of April 27 and as burglars did not get your money I shall reopen my Studio on May 9, 1904, and see if I can get some of it."

Whitcomb’s good nature was challenged again just one short month later when his studio and the Grocery downstairs were badly damaged by fire. His insurance money was late in coming and he lost nearly the entire summer’s income. Undaunted, he rebuilt and remodeled the studio while his wife Inez, traveled alone to Boston to study new photography and finishing techniques. The studio reopened at the end of August.

Albion Moody was sick for several months during 1904. His daughter went to work in the Healy Studio near the train depot for the summer. In December of 1904 Moody announced his intention to go into the poultry business. He did not work in his studio during most of 1905. The Kennebunk Register that year lists both Albion and Lillie as mill operators. Whitcomb is the only photographer listed in Kennebunk in 1905.

During the summer of 1905 Whitcomb’s business was good enough to warrant a second location, inside the store of G. B. Carll in Kennebunkport. He hired Miss Lucas of Kennebunk to clerk his "branch studio". His work was very well received in Kennebunkport and the location suited him. On November 1, 1905 Whitcomb sold his business in Kennebunk to Lillie Moody including cameras, furniture, backgrounds and negatives and Moody’s studio at the bridge was dismantled. Albion moved into Whitcomb’s studio next door to the bank and advertised that he was ready to work again and that he had all of Whitcomb’s fancy equipment and all of his negatives. "Anyone who has had pictures taken by Whitcomb can now buy prints from me" he promised in the Kennebunk Enterprise. Moody’s new studio remained open for another year and in 1907 the building was torn down. Many of the photographs of Kennebunk in the very early 1900s that have been attributed to Albion Moody were actually taken by Whitcomb. The origin of any photograph that is identified to be from 1902 or later must be questioned.

Byron and Inez were looking ahead to new challenges in Kennebunkport. The carpentry skills that had supported his family when he was a boy were put back to work on a new studio building on Ocean Avenue much admired for its style. It had a showroom on the first floor and a studio on the second with skylights and decks that hung out over the river. The Whitcomb Studio was opened in the spring of 1906. A very successful business, it remained in the same location on Ocean Avenue for 21 years but B. J. Whitcomb’s work was missed in Kennebunk. The editor of "The Local News" lamented his relocation and hoped he would someday return to Kennebunk. In 1910 Whitcomb built what was referred to at the time as The Whitcomb Building on Main Street in Kennebunk and hired clerks to attend to his second location. He sold the building and possibly more negatives to photographer L. G. Gerry in 1914. The Whitcombs lived on School Street in Kennebunkport until 1927 when Inez’s father died and the family moved to Greenfield, Ma, to run his business. They kept a place here and visited often during the summer. Inez, who had been an active member of the Olympian Club for many years and a champion for women’s rights died in 1938. Byron sold the business in Greenfield and spent every summer here until his death in 1944.

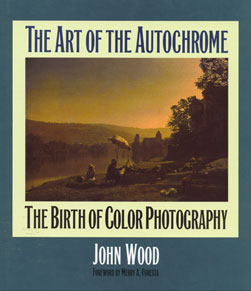

In 1906 while the Whitcombs were opening their studio in Kennebunkport the Lumiere brothers in Lyon, France were developing a process to capture color images called Autochromes. Tiny grains of transparent potato starch were dyed orange, violet and green. The colored grains were then mixed and dusted onto glass plates. Pressure was applied to rupture the cells of starch and then layers of emulsion and sealers were applied to the mosaic of transparent color. When an image was photographed through the potato starch filter complementary colored light would pass through each grain while all other light would be reflected. This produced a negative image on glass in colors exactly opposite the image on the color wheel. The negative would be inverted and an accurately colored positive glass transparency would result. When done well by an artist’s eye the images were not unlike an impressionist painting. Photohistorians claim that the subtle beauty of these color images has not been attained through any other process to this day. Unfortunately the process was expensive and impractical for professional photographers as each image was one of a kind and could not be reproduced. The colors could only be appreciated when viewed with a projector and through the years many have been overlooked as glass negatives. With the advent of home scanners and digital imaging a new appreciation for Autochromes as an art form has emerged.

In

1985 photohistorian, Alan Johanson purchased a box of fifty B. J. Whitcomb

Autochromes at an antique store in Amarillo, Texas. He was overwhelmed by

the artistry of the images of Kennebunkport in the early 1900s. In his

scholarly book "The Art of the Autochrome", John Wood describes Whitcomb as

a master of the art. He writes "there is no one in photography whose work is

exactly comparable to Whitcomb’s. One must look to Frank Benson, Edmond

Tarbell, William Paxton, those painters of the Boston school, their ethereal

women caught up in soft color and elegant interiors, in a "landscape of

pleasure," to find anything comparable."

The Kennebunkport Historical Society owns several hundred of Whitcomb’s black and white glass negatives that were donated by Virginia Adolph, a subsequent owner of the studio building on Ocean Avenue that unfortunately burned in 1967 when it was the the SeaGull Restaurant. The collection includes images of Kennebunk, Kennebunkport, Boston and Vermont as well as portraits of studio customers and Whitcomb family members.

Please search your attics. Do you have an original Whitcomb Autochrome? We would love to scan it for our collection. The Society also has the technology to scan and invert glass negative images and then produce high quality prints of them on photographic paper. These fragile works of art that document the history of the Kennebunks must be preserved. Exposure to cold, heat and moisture jeopardize the emulsion on the glass. Each plate should be stored in an acid-free sleeve standing on its shortest end and placed in a heavy box that is close to the size of the plates and

Many thanks to the Brick Store Museum and its archivists, Ros Magnuson and Kathy Ostrander for sharing the deed from the Whitcombs to Lillie Moody and for spending hours with me at the Kennebunk Free Library reading old newspapers that have yet to be microfilmed.

Sharon Cummins

This article was originally published in The Log, Kennebunkport Historical Society's quarterly publication. Copyright 2001-2006 Sharon Cummins